Benefits of Tissue Analysis Implementing a Tissue Analysis Program Collecting Samples Interpreting Test Results Nutrient Considerations More Info

Paul Schreiner, USDA-ARS and Patty Skinkis, Oregon State University

Managing and understanding grapevine nutrition can be a daunting task. Mineral nutrients are important to the entire vine as they play vital roles in plant biochemistry. An effective nutrient management program for vineyards requires good records of fertilizer and irrigation inputs, vigor assessment, yield, and interpretations of soil and plant tissue test results.

Soil testing alone is not generally useful in predicting vine nutrient status, due to a variety of issues such as differences in nutrient uptake or requirements of different varieties, clones and rootstocks, differing irrigation and soil management practices, and the plasticity of vine roots to explore soils in different environments. In addition, grapevines can store significant quantities of some nutrients to overcome short term deficits of soil supply, and this ability increases with vine age. For example, more than 50 percent of the canopy nitrogen (N) and phosphorus (P) came from stored reserves in the roots and trunks of non-irrigated mature ‘Pinot noir’ vines studied in Oregon (Schreiner et al., 2006). Soil analysis is useful in monitoring changes through multiple years, including pH and soil organic matter that can impact nutrient supply in soil. Soil analysis is particularly useful in determining potential vineyard planting sites and soil modifications needed before planting a vineyard. In general, however, yearly soil tests are not recommended for perennial crops.

Plant tissue testing is the preferred method of monitoring the nutritional health of vineyards. Tissue test results indicate nutrient status of vines, and they can be effective in identifying extremes, whether at levels of deficiency or toxicity. When samples are systematically collected during a period of years, tissue test results can be a valuable tool to manage the nutritional status of your vines to help identify problems. It is important to understand and correctly interpret tissue analysis data.

What do tissue nutrient test results tell you?

The data received in a plant tissue analysis report is the nutrient concentration; the amount of each nutrient per amount of petiole or leaf blade mass. Some may assume that nutrient concentrations equal nutrient uptake. However, this is not always true. The only way to be sure about nutrient uptake is to monitor the content of nutrients during the course of the growing season and relate nutrient content to growth differences. Rapid growth can dilute the concentration of nutrients in leaves and petioles. Tissue tests are much more meaningful to growers if some measure of plant growth is taken near the time of sample collection. This can be as simple as an estimate of shoot length at bloom. Results from tissue analysis are most useful when combined with other information from your site such as previous and current season’s growth, weather conditions, recent inputs to the vines (fertilizer, irrigation, tillage), and past experience with the particular vineyard or block.

Interpretation of tissue analysis results is not a simple process because plant mineral nutrition and the impact on vine physiology are complex. If an element appears to be deficient, closer inspection of the vines is warranted. Begin looking carefully for signs of deficiency symptoms. If deficiency symptoms appear, detailed sampling and tissue analysis should be considered. Do not rely on visual symptoms alone as nutrient imbalance symptoms can look similar to each other or to non-nutritionally related problems. Be sure to collect samples from unaffected vines in addition to affected vines for comparison to confirm a nutrient deficiency.

What to consider when implementing a tissue analysis program

1) Be as consistent as possible with respect to vine phenology (growth stage) when collecting tissue samples for nutrient analysis. Nutrient concentrations in leaves and petioles alike can change rapidly during the growing season. Time of sample collection is critical for getting accurate data from year to year. For example, research indicates that P decreases very rapidly from bloom to véraison. Be sure to collect samples at the same growth stage each year. (See number 5 below.)

2) Monitor the same areas within specific vineyards or blocks. To do this, designate and flag specific rows within a block that are revisited yearly. This can vastly improve the consistency of tissue analysis. Such sampling may be more important in hillside vineyards, where there can be great variability in soils across the slope.

3) If you would like to monitor large blocks with a single sample, then collect petiole or leaf blades in a systematic way across the area and be consistent from year to year. For example, collect one petiole or leaf blade from a typical vine located every five posts from every 5th row, avoiding rows close to the border of the block. A single sample should represent no more than 5 acres.

4) Collect and submit separate samples from problem areas where you suspect that vines are weak or otherwise lag behind, such as low lying areas that may develop more slowly during the season due to cooler temperatures, or areas with obviously different soil types. Be sure to keep samples separate by rootstock or cultivar to allow for the best interpretation of nutrient analysis.

5) Determine which times to take the sample. Sampling is often done at bloom and/or véraison. Generally, petiole samples taken at bloom give a good indication of micronutrient status. However, véraison sampling is more indicative of the status of the macronutrients nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium (N, P, and K). In general, véraison or ripening samples are better to diagnose N, P, and K problems because these elements are mobile within the plant and/or are at very high levels at bloom. Many growers like collecting samples at bloom so they can correct problems in the current year. This is most useful for micronutrients, because deficiencies can be amended in the current season with foliar sprays. For macronutrients, however, correction during the current year is unlikely as nutrient analysis takes time and results need to be interpreted correctly to warrant fertilizer applications. A whole vine nutrient uptake study showed peak N and P uptake occurs at bloom and declines thereafter (Schreiner et al., 2006). Therefore, it is not likely that one can affect the macronutrients in the current season.

6) Determine which tissue to sample: leaf blade or petiole. Generally, petiole samples give an indication of potassium, chlorine, and sodium (K, Cl, and Na) deficiencies/toxicities. Leaf blade samples give a much better indication of N than petiole samples, but also magnesium (Mg), zinc (Zn), boron (B), calcium (Ca), copper (Cu), and manganese (Mn) deficiencies or toxicities. Petiole samples are easier to handle and collect in large quantities and provide a good average for the block sampled. The leaf blade is the working organ of the plant and relates better to physiology of vines. Analyzing both leaf blades and petioles can be useful to diagnose certain issues and specific deficiencies/toxicities.

Collection of tissue samples

Bloom (60 percent to 70 percent cap fall) – For petiole analysis, collect 60 to 100 petioles of leaves at the same node as a cluster. Cut off and discard the leaf blades, rinse in water, blot dry, put in paper bags, and dry in an oven at 125ºF to 160ºF, if possible. If they cannot be dried immediately, get the samples to the lab as soon as possible. For leaf blades, collect 20 to 40, remove and discard the petiole, rinse in water and blot dry on paper towels. Dry the leaf blades quickly after collection because they mold much faster than petioles.

Véraison (50 percent of berries colored) – Collect 60 to 100 petioles and/or leaf blades in pairs – one opposite cluster and one from a recently expanded leaf from each vine sampled. Treat as outlined above.

Interpretation of tissue nutrient test results

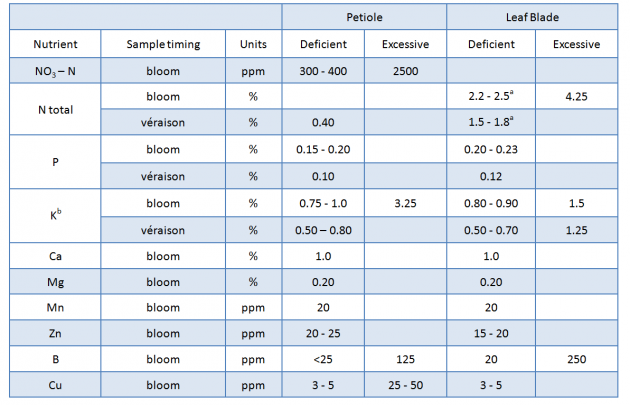

Table 1 provides a guide for interpreting tissue nutrient concentrations for grapevines. The values in this table were derived from numerous sources, including research conducted in Oregon on wine grape nutrition, and represent the current understanding of sufficiency or deficiency for wine grapes.

Table 1. Nutrient Guidelines for Wine Grapes

Nutrient Considerations

1) Nitrogen (N): Surprisingly, N can be a limiting nutrient in some vineyards, particularly those on lighter soils with low organic matter. Nitrogen status must be interpreted with respect to vine vegetative vigor and assessment of the visual characteristics of the vine. If N appears to be deficient based on tissue analysis, it is not advisable to give N to vines with high vigor. Adding some N fertilizer or using N-fixing cover crops should only be considered if vines have low vigor and low N levels upon analysis. Excessive nitrogen at bloom has been observed to cause inflorescence necrosis. In addition, low grape must N concentrations (YAN) are not always associated with low levels of N in the vine.

2) Phosphorus (P): In some cases, low soil P does not always result in low vine P due to the influence of mycorrhizal fungi. However, because P is important for flower and fruit formation and differentiation, keep a close watch on P levels. Low P status in grapevines may be best diagnosed by comparing leaf and petiole P at véraison because P will generally occur at a similar or higher concentration in petioles compared to leaf blades when P is adequate.

3) Potassium (K): Low K levels can be a result of drought and/or overcropping vines the previous season. Amendments of vineyard K levels must be approached with care. Grape clusters are a strong sink for K. If a vineyard is cropped to very low yields, it is easy to overapply K fertilizers, which may lead to increased pH in musts. High K in musts can also be associated with vigorous, shaded canopies and can be corrected by better canopy management.

4) Boron (B): Some growing regions have low B due to low B levels in soil. In these cases, growers can apply foliar sprays of B to the vine canopy in spring, prior to bloom or later in the season, post-harvest. It is recommended to apply these sprays at low doses to prevent toxicity.

5) Zinc (Zn): Low Zn can be associated with high Mg levels. Foliar sprays of Zn are applied in dormancy with a follow-up spring spray if deficiency is severe.

6) Iron (Fe): Fe is difficult to diagnose based on tissue tests. The form of Fe in the leaf is most important, and leaf size is often reduced when Fe is limiting. Low Fe is diagnosed by a combination of interveinal leaf chlorosis (bleaching) and high soil pH.

References:

Christensen P. 2000. Use of Tissue Analysis in Viticulture. UC Extension Publication NG10-00.

Schreiner R.P., C.F. Scagel and J. Baham. 2006. Nutrient uptake and allocation in a mature ‘Pinot noir’ vineyard in Oregon. HortScience 41:336-345.

Skinkis, P and R.P. Schreiner. 2010. Grapevine nutrition online module. Oregon State University Extension.

Schreiner, R.P., J. Lee and P.A. Skinkis. N, P, and K supply to Pinot noir grapevines: Impact on vine nutrient status, growth, physiology, and yield. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 64: 26-38

Recommended Resources

Please visit the online module Grapevine Nutrition to learn more about macro- and micronutrients, symptoms of deficiency and toxicity, vine nutrition, managing nutrition, and more.

Sampling Guide for Nutrient Assessment of Irrigated Vineyards in the Pacific Northwest

Vine Nutrition Effects on Grape and Wine Quality, Washington State University

Petiole Gathering video, Cornell University

Grapevine Mineral Nutrition PowerPoint presentation, University of California

Reviewed by Eric Stafne, Mississippi State University and Bruce Bordelon, Purdue University