Trunk Shoots Tendrils & Buds Suckers & Watersprouts Canes More Info

Ed Hellman, Texas AgriLife Extension

The Trunk

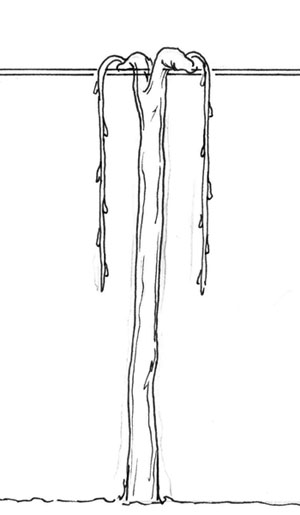

The trunk, which was formerly an individual shoot trained as the trunk in a young vine, becomes permanent and supports the above-ground vegetative (leaves and stems) and reproductive (flowers and fruits) structures of the vine. The height of the trunk varies with the training system selected. For cane-pruned training systems, the top of the trunk is referred to as the head. The height of the head is determined by pruning during the initial stages of training a young grapevine (or replacement trunk). The trunk of a mature vine will have arms, short branches from which canes and/or spurs originate, which are located in different positions depending on the system. Some training systems utilize cordons, semi-permanent branches of the trunk. Cordons are usually trained horizontally along a trellis wire, with spurs spaced at regular intervals along their length. Where bilateral training systems are used, the cordon is trained to either side of the trunk, and some growers refer to each of the two sides of the cordons as arms. Other systems utilize canes, one-year-old wood arising from arms and usually located near the head of the vine. Multiple trunks are often used in grape growing regions that are at risk for winter injury. The term “crown” refers to the basal region of the trunk slightly below and above the soil level.

Shoots and Canes

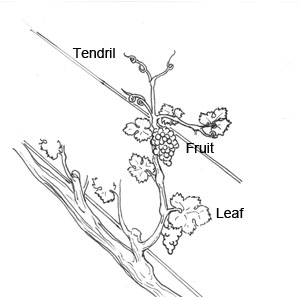

The shoot consists of stems, leaves, tendrils, and fruit and is the primary unit of vine growth and the principal focus of many vineyard management practices. Shoots arise from compound buds that are initiated around bloom during the previous growing season. Each compound bud can potentially produce more than one shoot. Primary shoots arise from primary buds (described below) and are normally the fruit-producing shoots on the vine. The main axis of the shoot consists of structural support tissues and conducting tissues to transport water, nutrients, and the products of photosynthesis. Arranged along the shoot in regular patterns are leaves, tendrils, flower or fruit clusters, and buds. General areas of the shoot are described as basal (closest to its point of origin), mid-shoot, and apex (tip). The term canopy is used to describe the collective arrangement of the vine’s shoots, leaves and fruit; some viticulturists also include the trunk, cordons and canes.

Shoot tip. The shoot has many points of growth that will be described in more detail below, but the main shoot growth in length occurs from the apical meristem, located at the shoot tip. New leaves and tendrils unfold from the tip as the shoot grows. Growth rate of the shoot varies during the season. Grapevine shoots do not stop expanding by forming a terminal bud as some plants do, but may continue to grow if there is sufficient heat, soil moisture, and nutrients.

Leaves. Leaves are produced at the apical meristem. The shoot produces two or more closely spaced bracts (small scale-like leaves) at its base before it produces the first true foliage leaf (Pratt, 1974). Leaves are attached at the slightly enlarged area on the shoot that is referred to as a node. The area between nodes is called the internode. The distance between nodes is an indicator of the rate of shoot growth, so internode length varies along the cane corresponding to varying growth rates during the season.

Leaves consist of the blade, the broad, flat part of the leaf designed to absorb sunlight and CO2 in the food manufacturing process of photosynthesis, and the petiole, the stem-like structure that connects the leaf to the shoot. The lower surface of leaf blade contains thousands of microscopic pores called stomata (singular = stomate), through which diffusion of CO2, O2, and water vapor occurs. Stomata are open in the light and closed in the dark. The petiole conducts water and food material to and from the leaf blade, and maintains the orientation of the leaf blade to perform its functions in photosynthesis.

Tendrils. The shoot also produces tendrils, slender structures that coil around smaller objects (i.e., trellis wires, small stakes, and other shoots) to provide support for growing shoots. Tendrils grow opposite a leaf at the node, except the first two or three leaves at the base of the shoot. Thereafter, tendrils can be found opposite leaves, skipping every third leaf. Flower clusters and tendrils have a common developmental origin (Mullins et al., 1992), so occasionally a few flowers will develop on the end of a tendril.

Buds. A bud is a growing point that develops in the leaf axil, the area just above the point of connection between the petiole and shoot. The single bud that develops in this area is described in botanical terms as an axillary bud. On grapevines, a bud develops in every leaf axil, including the inconspicuous basal bracts (scale-like leaves). In viticulture terminology, the two buds associated with a leaf are termed the lateral bud and the dormant bud (or latent bud). The lateral bud is the true axillary bud of the foliage leaf, and the dormant bud forms in the bract axil of the lateral bud. Because of their developmental association, the two buds are situated side-by-side in the main leaf axil. Each bud is a compound bud, containing three distinct growing points, each capable of producing a shoot. These are commonly referred to as the primary, secondary, and tertiary buds, respectively. At bud burst, the primary bud is typically the only bud that begins to grow. If the primary bud is damaged, then the secondary and/or tertiary buds are released from dormancy and grow in place of the primary bud. These secondary and tertiary buds generally have little to no fruit in comparison to the primary bud.

Suckers and Watersprouts. Latent buds embedded in older trunk and cordon wood may also produce shoots. Suckers are shoots that grow from the crown area of the trunk. Watersprout is sometimes used to refer to a shoot arising from the upper regions of the trunk or from cordons (Winkler et al., 1974). Buds growing from older wood are not newly initiated buds, but rather they developed on green shoots as axillary buds that never grew out. These latent buds can remain dormant indefinitely until an extreme event such as injury to the vine or very severe pruning stimulates renewed development and shoot growth (Winkler et al., 1974).

Suckers often arise from latent buds at underground node positions on the trunk. In routine vine management, suckers are removed early in the season before axillary buds can mature in basal bracts of the sucker shoots. Similarly, above-ground suckers are typically stripped off the trunk manually so a pruning stub does not remain to harbor additional latent buds that could produce more suckers in the following year.

Latent buds come into use when trunk, cordon, or spur renewal is necessary. Generally, numerous latent buds exist at the “renewal positions” (a pruning term) on the trunk or cordons. Dormant secondary and tertiary buds exist in the stubs that remain after canes or spurs have been removed by pruning.

Canes. The shoot enters a transitional phase, starting around veraison, when it begins to mature or ripen. Shoot maturation begins at the shoot base as periderm develops, starting at the shoot base, appearing initially as a yellow, smooth “skin”, and continues to form outward toward the shoot tip through the remainder of summer and fall. As periderm develops, it changes from yellow to brown, and becomes a dry, hard, smooth layer of bark. During shoot maturation, the cell walls of ray tissues thicken and there is an accumulation of starch (storage carbohydrates) in all living cells of the wood and bark (Mullins et al., 1992). Once the leaves fall from the vine at the beginning of the dormant season, the mature shoot is considered a cane.

The cane is the principal structure of concern in the dormant season, when pruning is employed to manage vine size and shape, and to control the quantity of potential crop in the coming season. Because a cane is simply a mature shoot, the same terms are used to describe its parts. Pruning severity is often described in terms of the number of buds retained per vine or bud count. This refers to the dormant buds, which in a single bud contains three growing points as described above. When considering a dormant cane, the buds located at the very base of a cane include secondary and tertiary growing points that give rise to the axillary buds of the shoot’s basal bracts (Pratt, 1974). It should be noted that the most basal buds on a cane are generally not fruitful and do not grow out, so they are not included in bud counts. These are often referred to as non-count buds during the pruning process.

Canes can be pruned to varying lengths, and when they consist of only one to four buds, they are referred to as spurs, or often, fruiting spurs. Grapevine spurs should not be confused with true spurs produced by apple, cherry, and other fruit trees, which are the natural fruit-bearing structures of these trees. On grapevines, spurs are created by short-pruning of canes. Training systems that use cane-pruning also use spurs for the purpose of growing shoots to be trained for fruiting canes in the following season. These spurs are known as renewal spurs, indicating their role in replacing the arms.

References:

Mullins, M. G., A. Bouquet, and L. E. Williams. 1992. Biology of the Grapevine. Cambridge University Press.

Pratt, C. 1974. Vegetative anatomy in cultivated grapes. A review. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture 25:131-150.

Winkler, A.J., J.A. Cook, W.M. Kliewer, and L.L. Lider. 1974. General Viticulture. University of California Press. Berkeley, California.

Recommended Resources

Grapevine Structure and Function, Texas A&M University

Grapevine Anatomy and Dormant Pruning, Adobe Breeze presentation, Virginia Tech

Cane Pruning Grapevines video and Spur Pruning Grapevines video, Oregon State University

Wine Grapevine Structure, pp 4-5 in ”’Winegrape Varieties in California”, University of California

Anatomy of Winter Injury and Recovery, Cornell University

Parts of the Grape Vine: Roots

Parts of the Grape Vine: Flowers and Fruit

Reviewed by Tim Martinson, Cornell University, and Patty Skinkis, Oregon State University