Scion Wood Preparation Chip Budding Prep Chip Budding Process Care for Grafted Vines Advantages & Disadvantages For more information

Mercy Olmstead, University of Florida and Markus Keller, Washington State University

Introduction

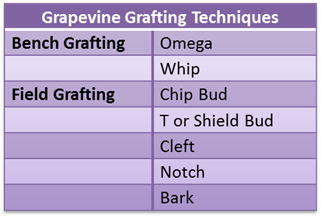

Chip bud grafting is a convenient method for changing varieties or top-working grapevines in a vineyard. This may be conducted to allow growers to change the cultivar to meet increased consumer demand, adapt to changing market conditions, and garner increased economic gains. Chip bud grafting is a form of field grafting, conducted on vines already planted in a vineyard. This is different from bench grafting, which is conducted on dormant plant materials (Table 1; Figure 1).

Table 1. Different grafting techniques used in producing grapevines with a rootstock.

Grafting combines two plant portions–the scion and rootstock (Figure 2). The graft union is covered with grafting tape to protect the new graft union and ensure that the scion and rootstock have enough contact to form callus. Callus is formed during the grafting process that connects the two plant parts, creating one cohesive stem with continuous transport tissues (xylem and phloem). Xylem and phloem are differentiated within the graft union from callus cells.

Scion Wood Preparation

Top-working a vineyard requires advanced planning of at least one year. Scion wood should be collected when dormant in late fall (November) or early winter (December) to ensure there is optimum carbohydrate storage in the wood for viability of the wood for future grafting and growth. Collect scion wood from healthy grapevines known to be “clean” (free of virus–preferably tested to be virus-free) and avoid grapevines that show symptoms of disease or insect damage. Selection of scion budwood should be pencil-thick in diameter (9/16-inch to 3/8-inch), straight, uniformly round, and well-lignified (Figure 3). The internode length should be approximately 2.5 inches to avoid selecting wood that grew too vigorously or weak, and can serve as an indicator of wood carbohydrates and/or bud viability. Cuttings of scion wood should include four to five buds for a total of 12 to 16 inches to facilitate easy storage.

Once collected, scion wood can be bundled with 50 to 100 cuttings/bundle and treated to reduce the incidence of certain pests and diseases while in storage (e.g., pathogenic fungi, crown gall bacteria and certain phytoplasmas). This can be done by placing the wood in a water bath at 122ºF (50ºC) for 30 minutes. After the heat treatment, rinse the wood in cool water to prevent tissue damage. Heat treatments can damage grapevine buds if scion wood is collected late (early spring); therefore, it is important that scion wood is collected in the late fall. If hot water treatments are not possible, fungicidal drenches/dips can be used, such as hydrogen peroxide type products (ZeroTol).

Preparing Grapevines for Chip Budding

Grapevines should be prepared for chip budding during the normal time period of dormant pruning by cutting back the existing grapevine trunk to encourage the growth of suckers. In the spring, the strongest two suckers should be trained up to the cordon wire and attached with string or vinyl tape. These will become the new rootstock for the new variety.

As the suckers grow, disbud all but the top two leaves to provide transpiration for the new shoot (Figure 4). This will allow water and nutrients to flow up the shoot and through the new graft union after budding. Prevent any additional lateral growth from buds on the sucker, as these will only serve to draw carbohydrates away from the new shoot growth.

Chip Budding Process

Preparation of the bud: To begin the chip budding process, scion wood can be removed from cold storage and unwrapped from bundles. Soak the scion wood for one to two days to rehydrate the tissue. Chip buds should be made with two cuts with the initial cut being made with the knife perpendicular to the wood surface, approximately 1/8-inch (1 mm) from the base of the bud. The second cut should be made with the knife placed approximately 1/4-inch (3 mm) above the cut, drawing the knife smoothly to the first cut around the back of the bud (Figure 5). Be sure to cut buds on the day of grafting or just before grafting in-field to avoid dehydration. Cut buds cannot be stored, so cut only enough buds for the grafting activities for that day.

Preparation of the Rootstock: To prepare the trained sucker in the field, make cuts in the sucker to mirror chip buds previously cut from scion wood. Chip buds are most successful if the diameter of the chip bud and the recipient stock are matched carefully. Insert the chip buds onto the new rootstock, and wrap tightly with grafting tape to ensure a tight connection. Buds must have a tight connection to form callus and strongly develop the graft union. White or transparent grafting tape will help to reflect solar radiation.

The location of the graft union is very important in areas that are prone to fall and spring frosts. Graft unions made lower to the ground where radiation freezes are common are prone to failure, compared to those made higher on the rootstock. Chip buds that are placed higher on the rootstock are also much easier to train to the cordon wire than those placed lower.

New growth should emerge from the newly grafted bud approximately one to two weeks after budding (Figure 6). Growth from the existing rootstock will tend to grow more quickly than that from the new bud, so remove this growth quickly to encourage growth of the new scion. Keep the two existing leaves on the rootstock until there is 6 inches (~15 cm) of new scion growth. At this point, the existing rootstock can be removed to about 1 inch (2.5 cm) above the graft union.

Caring for Grafted Vines

Newly grafted grapevines should be cared for in the same manner as newly planted vines. Irrigate, fertilize, and control weeds as appropriate for a young vineyard in your region. With the removal of a large portion of the canopy, the much larger root system can cause vigorous canopy growth for the first two years. Buds that break from the rootstock should be removed to direct growth to the scion. Encourage hardening off in the autumn by slowly reducing irrigation and fertilization, as this new graft union is particularly sensitive to cold injury.

Encourage growth to develop the new training system. To prevent vine stress, remove any crop that sets the year after grafting. In the second year after grafting, a small crop can be harvested, and full crop potential can be achieved in the third year.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Chip Budding Grapevines

Advantages

- Ability to change cultivars to meet market demands without removal and replanting of vineyard blocks.

- Ability to return to original cultivar, particularly in areas where varieties can be grown own-rooted.

- Easier and faster than other methods of field grafting.

- Significant yield can be realized in third year, compared to fifth year in complete vineyard replanting.

Disadvantages

- Requires experienced grafting crews for best results.

- Graft success can be variable, depending upon experience of grafting crew.

- Chip bud grafting during summer months requires adequate storage of scion wood until use.

Related Links

Chip Bud Grafting in Washington State Vineyards, Washington State University

Reviewed by Jodi Creasap Gee, Cornell University

and Patty Skinkis, Oregon State University