The Basics Vine-Dictated Balance Viticulturist-Dictated Balance Unbalanced Vines How to Measure Vine Balance More information

Patty Skinkis, Oregon State University

The Basics

Vine balance is the central concept in the study of viticulture where vine physiology and vineyard production merge. This concept was introduced long ago and has been further defined by viticulture researchers around the world. Examples of vine balance are central to vineyard production and have arisen from research during the past century. Nelson Shaulis developed the balanced pruning method which evaluates pruning decisions based on bringing a vine into balance (Shaulis, 1966). Numerous researchers have further defined this concept of balance by trying to understand the impact of production practices on sustained vine growth and development, including impacts of canopy management, effect on flowering and fruit set, influence on dormancy and winter hardiness, yield, and fruit quality. Studies continue today to further understand production and physiology as related to vine balance.

The concept of vine balance is often easier to understand in theory than it is to perfect in practice. Trained viticulturists learn that vine balance is defined as the state at which vegetative and reproductive growth lead to the most “balanced” vine. Unlike wine balance, which is a more subjective concept, vine balance measures vine growth capacity through fruit yields and vine size (leaf area or dormant pruning weight), and has some generalized guidelines to understand whether a vine is in good shape (i.e., vigorous or weak). In the most straightforward sense, vine balance has been defined and calculated as the ratio between vine yield and vine size, representing reproductive and vegetative production of the vine, respectively. This relationship is known as crop load and is calculated by taking a vine’s yield and dividing by the dormant pruning weight. There are two different equations for crop load, the Ravaz Index and the Growth-Yield Relationship. The distinction between the two equations is as follows:

- Ravaz index = Yield/Pruning Weight, where the yield from the current harvest is used against the pruning weight in the following dormant season. Note: This is the most commonly used crop load calculation.

- Growth-Yield Relationship = Yield/Pruning Weight, where the pruning weight from the dormant season is compared against the yield of the following season.

The resulting number is a ratio, and, therefore, is without units. Research to date indicates that vine balance is obtained within the range of five to ten for Vitis vinifera. This range is rather large but is required, as there are different levels of vine balance based on the vineyard site and production goals. Crop load ratios that are lower than the optimum range are under-cropped (low yields and larger vine), while numbers at the high end of the spectrum are over-cropped (more fruit and smaller vine). Ultimately, being at either end of the spectrum can lead to unsustainable vine growth and production.

Vine leaf area is another metric that has been used for understanding vine balance, comparing yields to leaf area. Many trials have been conducted over the years to define leaf area required to ripen fruit adequately. Kliewer and Dokoozlian (2005) found that 0.5-1.2 m2 leaf area was required to ripen 1 kg of fruit, depending on the training system. While this metric is important to understanding vine size, it is less practical to monitor, as these data are far more tedious and time consuming to gather than pruning weights. Also, leaf areas are often highly manipulated in the vineyard through canopy management and can be harder to interpret in vineyard management records.

Vine balance is complex and dictated by the soil, environment, and overall production capacity of the vineyard. Since there are so many factors that play a role in vine balance, there are no clear guidelines as to how to create a balanced vine across all sites; rather, the methods for achieving vine balance depend on the following factors:

- Environment

- Soils

- Water availability

- Cultivar

- Rootstock

- Vineyard design (spacing, trellis system)

- Vineyard floor management

- Nutrition

- Diseases and pests

- Management practices

- Production goals

Vine-Dictated Balance

The grapevine, like other organisms, will reflect its environment. Management methods play a role in vine balance but are secondary to the inherent growth potential of a vine based on the vineyard site (soils, precipitation, climate) and the plant material (cultivar and rootstock). Vineyards on deep, fertile soils with good water holding capacity will be able to grow larger vines and produce higher yields than vineyards on a site with shallow or coarse soils with poor water holding capacity. That is, those vines with relatively unlimited resources in soil moisture, mineral nutrition, and climate (sun and heat units) will be able to produce the maximum amount of carbon for fruit production, vegetative growth and reserves for the next season’s growth. Conversely, those vines with limited resources will be weaker and have less carbon available for the current season’s growth and less in reserves for the following seasons. In these divergent scenarios, vine spacing, pruning, trellis, and yields will need to be determined to allow the vine to reach a balance of canopy and fruit growth on that site. The vine-dictated balance will ultimately determine the vineyard design and management decisions made.

Viticulturist-Dictated Balance

The viticulturist-dictated balance of the vineyard is determined by the production goals, vineyard management methods, and economics of the business. Those production practices that do not adhere to a vine’s production capacity will inevitably result in unsustainable vineyard production practices, as there will be reduced vine health and reduction in yields and/or fruit quality. For example, severely limiting vine yields through crop thinning for high quality winegrape production may be under-cropping vines to a point where they may become overly vigorous and may lead to problems such as poor fruitfulness/fruit set, shaded canopies, increased disease incidence and canopy management costs. In vineyards where there is competition for water resources by poor vineyard floor management and/or improper irrigation and high yields, there can be problems such as reduced fruit quality (lack of ripening), weak wood, poor bud fruitfulness, and poor bud break. Therefore, the vineyard balance really depends on the viticulturist reading the vine’s capacity and maximizing that production capacity and/or quality with reasonable and economic inputs.

Unbalanced Vines

Vines that are not balanced have significant changes in various factors, all of which can affect vine size and yields. Vines that are overly vigorous often have poor bud fruitfulness, reduced fruit set, and lower yields. Unless adequately managed, these vines can spiral into an overly vegetative state. In addition, these vines can have poor winter hardiness and low bud survival in areas with more severe winters. Simply cutting off excess canopy of vigorous vines through hedging and leaf removal can help modify the microclimate, but these methods do not bring a vine back into balance. Care must be taken to address the cause of excessive vine vigor, which may be fertility, soil moisture, and/or cropping level.

Weak vines can experience similar maladies as overly vigorous vines. There can be reduced bud fruitfulness, leading to reduced yields. Weak vines may also have reduced bud break in spring and poor shoot development due to limited reserves for adequate shoot growth in spring and limited carbon availability during the growing season. In very weak vines, shoot growth can be stunted in early spring and into the growing season. As a result, shoots may not grow enough to support the fruit and will require that the crop be thinned to allow for the reserves to be replenished with carbon.

Over- or under-cropping vines can lead to reduced or increased vine vigor, respectively. However, crop level alone is not the only factor leading to high or low vigor vines.

How to Measure Vine Balance

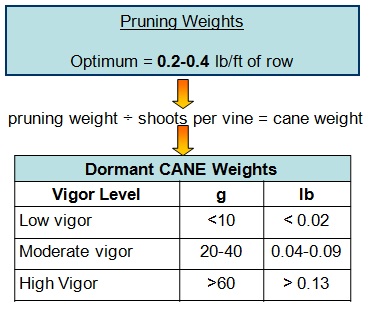

Vine balance is most directly measured through pruning weights and yields at harvest. The dormant pruning weights of vines represent “vine size” and can indicate whether a vine is of high, moderate, or low vigor. Cane weights are sometimes a better indicator of vine size, as this metric considers individual shoot weight. This is an easy calculation that considers the vine pruning weight divided by the number of shoots per vine. Although vineyards may be hedged and manipulated during the growing season, pruning weights still prove to be beneficial in determining and comparing vine size between vineyards and vineyard blocks. The table below lists some basic metrics known to be optimum for dormant pruning weights.

Harvest yields are critical to monitor to compare to pruning weights. This measurement is required to calculate crop load (yield/pruning weight). Comparing the crop load data across seasons will help determine the impact of management practices on production and fruit quality. Keeping records of vine yield data at the lag phase (known as lag phase weights) is also important to interpreting vineyard data and crop load, particularly if crop is removed during the later part of the season. This provides some insight into fruit set, the increase factor from lag to harvest, and interpreting the true crop level of the vines.

Summary

The trained viticulturist can easily see when a vine is in balance. However, it is important for observations to be documented by vineyard records including pruning weights, yields, crop load (Ravaz index), nutrition records, pest management, etc. All of these factors need to be considered in the vineyard production system because they play an important role in vine balance, fruit quality, and vineyard health.

Literature Cited

Kliewer W.M., and N.K. Dokoozlian. 2005. Leaf Area/Crop Weight Ratios of Grapevines: Influence on Fruit Composition and Wine Quality. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture 56:170-181.

Ravaz, L. 1903. Sur la brunissure de la vigne. Les Comptes Rendus de l’Académie des Sciences 136:1276-1278.

Shaulis, N. J., T. D. Jordan and J. P. Tomkins. 1966. Cultural practices for New York vineyards. Cornell Extension Bulletin 805: 33-34.

Recommended Resources

Howell, G.S. 2001. Sustainable Grape Productivity and the Growth-Yield Relationship: A Review. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture 52:165-174.

Vine Size and Balance and Balanced Pruning, Penn State University

Crop Thinning: Cluster Thinning or Cluster Removal

Overview of Vineyard Floor Management

Vine Balance and the Role of Vineyard Design

Monitoring Grapevine Nutrition

Reviewed by Jodi Creasap Gee, Cornell University and Bruce Bordelon, Purdue University